Hacker

Ethics of ethical hacking: A pentesting team’s guide (& checklist)

A pentesting team manager’s practical checklist to help junior employees get up to speed on the ethics of hacking.

Table of Contents

We’re all familiar with “ethical hacker” as a collective term for security professionals who are authorized to find vulnerabilities in software and systems.

As much as that may seem straightforward, many people who use this term probably don’t have a good understanding of what the “ethical” part of the name means. And, more generally, what is meant when talking about “ethics” and “ethical codes.”

It is also easy to confuse a personal moral code with a professional code of ethics.

Personal vs. professional ethics in cybersecurity

Take a situation where an ethical hacker is carrying out a penetration test for a client and has agreed to a non-disclosure agreement that requires all information about the client to be kept confidential.

During the engagement, the ethical hacker finds evidence that the customer’s product is manufactured in a different country than the one publicly claimed by the company.

The ethical hacker’s personal moral code might drive them to report this fact to the relevant authorities. However, the legal agreement signed and the professional code of practice they operate under obliges them to keep any of the client’s information discovered during an engagement confidential.

Professional codes of ethics aim to give a set of rules to operate by that protect:

-

The ethical hackers themselves.

-

The craft and profession of hacking or pentesting.

-

A client's systems and software.

-

And the general public.

But as we saw with the scenario outlined above, how one applies the rules in practice is not always clear-cut.

In the area of penetration testing, ethics and operating legally are especially important because a tester is effectively doing something that would be considered illegal in most countries if it weren’t for the explicit permission of the client.

Even with permission, it is easy for a penetration tester’s actions to be misinterpreted. Or for the tester to take an action that the client considers inappropriate.

Upskill & certify your team for specific roles

-

Rapidly close skills gaps: Combine theory and practice with browser-based, interactive content tailored for defensive and offensive security roles.

-

Stay ahead of the threat landscape: Give your team access to threat-based learning with real scenarios and real techniques from experienced and active professionals.

-

Onboard, develop, & upskill your team: Easily evaluate your team’s skills development and pair guided training with hands-on HTB Labs.

What are ethics in cybersecurity?

Ethics are a set of principles or rules that guide people on how to live in a way that distinguishes right from wrong. Especially when living and working with other people.

These rules are dependent in part on the particular culture that you live in, but some ethical principles are universal.

Ethics ensure that individuals act in a way that is, at the very least, not causing harm to others. At best, ethics encourage behavior that is usually in the best interest of a group or society as a whole.

Professions such as doctors, engineers, and security professionals are defined by the fact that their members operate according to a code of ethics, sometimes called a code of practice.

The professional cybersecurity organization (ISC)2 has a code of ethics that consists of four pillars:

-

Protect society, the common good, necessary public trust and confidence, and the infrastructure.

-

Act honorably, honestly, justly, responsibly, and legally.

-

Provide diligent and competent service to principals.

-

Advance and protect the profession.

These principles are sound in their aim to make it clear that cybersecurity professionals should act in a professional manner and not harm others.

They are still open to interpretation, especially when putting them into practice.

Other groups, such as the EC-Council, have a more detailed code of ethics that relates not only to the practice of penetration testing but also considerations around the certifications obtained from that group.

The fact that this code is more detailed helps in some ways in being more explicit, but it is harder to internalize a code that has nearly 30 different points.

Training teams to practice ethically

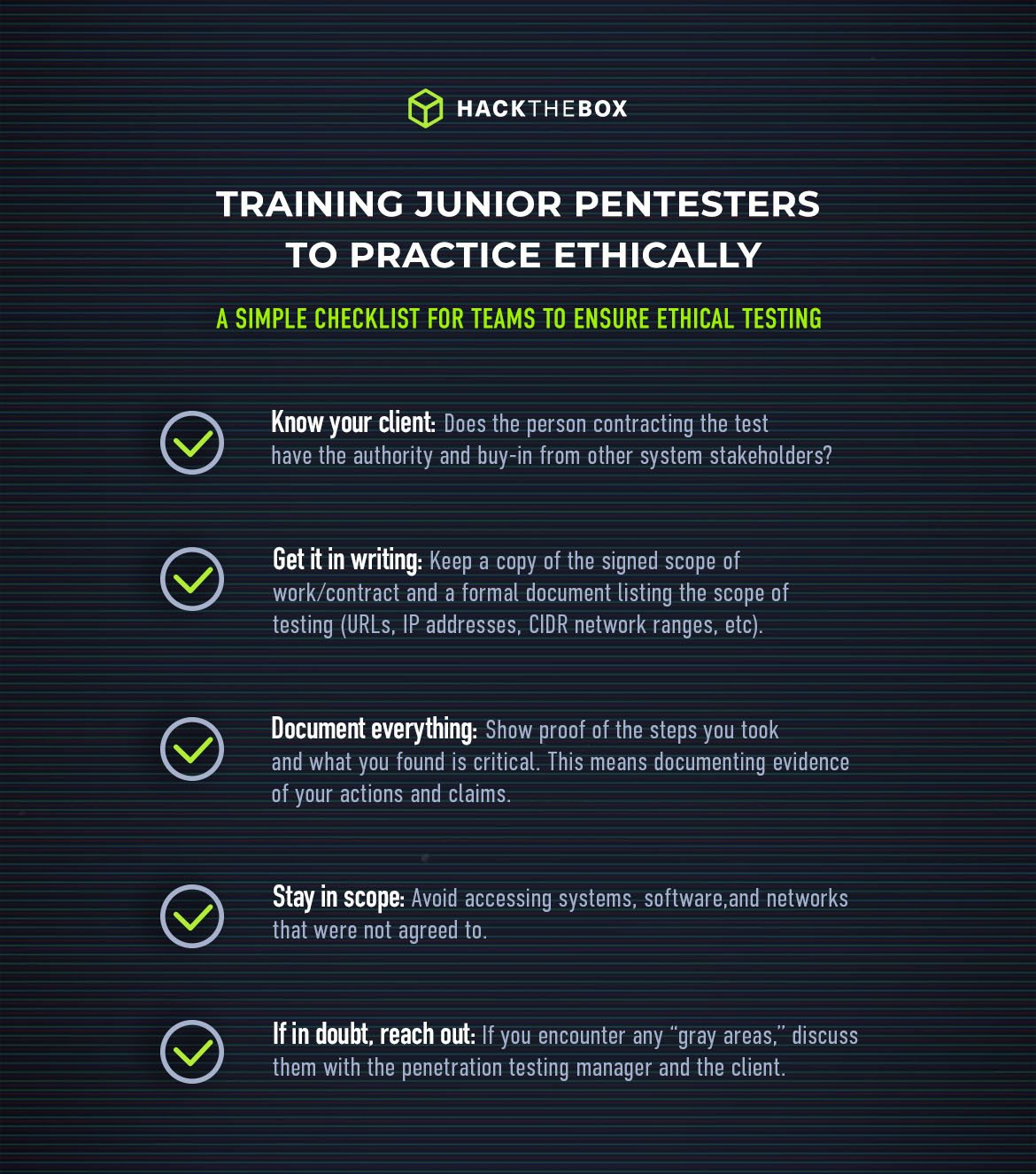

Know your client

Is the company contracting the work legitimate?

Whilst it may be a rare occurrence, criminal organizations are known to pose as legitimate organizations in order to get penetration testers to uncover vulnerabilities in a network they are targeting.

Equally important is the question of whether the person contracting the penetration test has the authority and buy-in from other system stakeholders to permit a penetration test.

This becomes increasingly problematic when the client wants to carry out a red-team style engagement without informing the security and IT teams of the company.

Get everything in writing

As mentioned in the HTB Academy training module:

“When working for any company, make sure that you have a copy of the signed scope of work/contract and a formal document listing the scope of testing (URLs, individual IP addresses, CIDR network ranges, wireless SSIDs, facilities for a physical assessment, or lists of email or phone numbers for social engineering engagements), also signed by the client. When in doubt, request additional approvals and documentation before beginning any testing.”

Another precaution that can be taken with initial documentation and contracts is to agree on the procedure should anything illegal be discovered during the penetration test.

This would include the order in which the discovery is communicated, and at what point law enforcement is informed.

Recommended read: CVE-2022-0492 explained

Work forensically (aka document everything)

A key aspect of the ethical principle of doing no harm is to make sure that your actions on the client’s network and systems will not damage running systems, stored data, or networks.

Your examination of the systems should not affect them unnecessarily. At the same time, showing proof of the steps you took and what you found is critical. This means writing down everything and obtaining evidence of your claims.

I have a principle that I call Proof-Any-Action (PAA), which consists of writing down each step with a reason behind why you're doing it.

Here you can assign a few checks to see if you are doing things right or not:

Is it gonna disclose/expose any confidential information? (Talk only to people who hired you or have been assigned to talk to you.)

Does it affect a known target (in scope)?

Is it gonna harm the system?

As a guideline, check if your answers to all the above questions are “no” because the job of a penetration tester is to find as many vulnerabilities as possible while staying within legal and ethical boundaries. An unethical hacker, on the other hand, only needs to find a single vulnerability.

We do not want to share anything with uninvolved third parties, nor do we want to harm the company. Our goal is to increase the cybersecurity of the company. Any other actions or omissions that lead to the opposite can be considered unethical.

It is not our actions and omissions that determine the environment of the consequences we have to deal with, but the reason what we did it for.

Valentin Dobrykov (Cry0l1t3), Training Development Lead, Hack The Box

Stay in scope

Through planning and constant checking during the tests, you should always be staying within the scope of the penetration test agreement. This means not accessing systems, software, and networks that were not agreed to.

Even within the agreed systems and environment, it is important to carry out the tests that were agreed to without straying from the scope.

If in doubt, reach out

If there are any ambiguities that occur during the testing process, these should be discussed with the penetration testing manager and the client.

If there are any changes to the scope or instructions as a result of these discussions, the documentation should be updated to reflect those new perspectives.

Practice being professional and ethical

One of the early Greek philosophers and the “father of ethics”, Socrates, believed that the only way to become ethical was not by reading or being told how to act in this way, but instead was to practice being ethical until it became habit.

This means questioning all actions when on a professional engagement and asking the question of whether it is ethical and legal.

Despite understanding the principles of acting ethically and professionally, there are still grey areas in cybersecurity that are possibly open to debate.

Disclosing a flaw that potentially could impact large numbers of people, which the product owner is not willing to address, for example, could be argued as a case of the protection of unwitting victims of a product’s failings that may justify the disclosure.

Security researchers in such a situation may find themselves pursued legally by the affected company despite it ultimately making their product more secure. In general, it is always better to act on the basis of permission from the system owner and, in the case of bug bounties, through an official bug bounty program.

Ethically, security professionals are not obligated to search and report or even act on any flaw in a product that they have not been asked to investigate.

For more guidance on improving your team’s onboarding process and knowledge, check out HTB Academy’s Pentesting job Role Path or penetration testing certification, CPTS.

|

Author bio: Valentin Dobrykov (Cry0l1t3), Training Development Lead, Hack The Box Valentin is the Training Development Lead for the Hack The Box Academy. He’s helped create courses like the Linux Fundamentals and OSINT: Corporate Recon modules. |

|

Author bio: David Glance (CyberMnemosyne), Senior Research Fellow, University of Western Australia Dr. David Glance is a cybersecurity consultant and Adjunct Senior Research Fellow at the University of Western Australia. He has taught and carried out research in the areas of cybersecurity, privacy, and electronic health. Dr. Glance has also worked in the finance and software industries for several years and has consulted in the areas of eHealth, cybersecurity and privacy for the OECD and WHO. He is the author of articles and books on cybersecurity. Feel free to connect with him on LinkedIn. |